Island History

Quarry Era (1902 – 1916)

One of the most profound changes to the history of Johnson’s Island was made by the quarrying operation. The ravages of the removal of the soil overburden and the underlying limestone destroyed most of the Union building sites. Also, the Federal docks, used by over 10,000 prisoners of war to arrive on, or depart from, the island during the War Between the States, were covered with over three feet of quarry spoils.

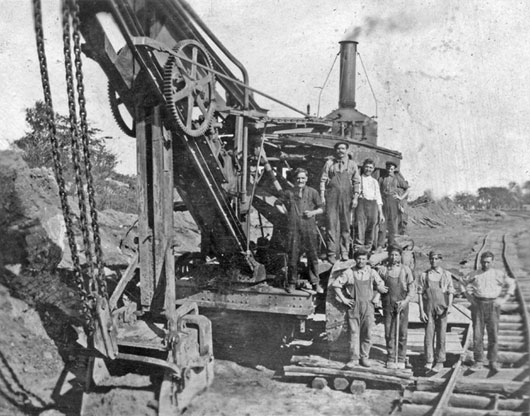

Courtesy of M. Demattia.

The Sandusky Register of December 18, 1900 carried an article announcing that “The old quarry on Johnson’s Island is again to be opened”. James H. Emrich and Charles Dick, owners of Johnson’s Island at that time, signed a contract with T. F. Gaynor, superintendent for breakwater contractor E. H. Koehan, for the removal of a huge amount of stone from the quarry. The stone was needed to repair and replace sections of the breakwater in Lorain, Ohio, which had been damaged by a storm.

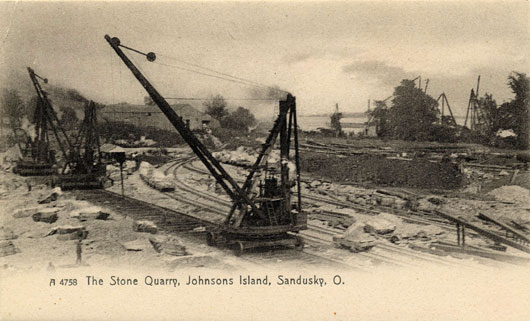

The actual stone removal work in the quarry did not begin immediately. Prior to the start of stone removal, it was necessary to improve the old docks and deepen the channel by dredging to allow lake scows to be loaded at the island. The quarry infrastructure, including railroad track and steam lines for drilling and running equipment, had to be completed. Approximately one-half mile of railroad track had to be laid to move equipment and stone cars around the 21.5-acre site and to the dock area for shipping.

Courtesy of M. DeMattia

Removal of the large stone slabs was very labor intensive even though there were 16 derricks to load the two trains that were constantly hauling stone to the docks. Initially, there were about 200 quarry workers. This number was to increase to 300 men after additional derricks and cranes were brought to the island. To expose the limestone, the soil and loose rock overburden was removed with steam shovels. The overburden was probably used to increase the size and elevation of the dock area to allow for storage of the rock slabs.

In order to house and feed the large number of workers, a small village was constructed and referred to as Gaynorville after the name of T. F. Gaynor who was Superintendent for the original contractor. The Sandusky Register in May of 1904 gave an excellent account of life in the village during the 1904 construction season. The workers occupied several houses, and some of the wives of workers did housekeeping and cooking for the workers. The article goes into depth about what was in the village. Since the workers lived on the island, a general store was opened, complete with a U.S. Post Office and saloon. The proprietor of the general store was E. Zannetti. At the general store, workers could buy a variety of pastas of different sizes and shapes as well as cheese to go with the pasta. The only visible remains of the village are some stonewalls and a cistern, most likely from the general store.

The article was very complimentary to the work force that was 80% Italian, with the remainder being Slavs and Tyrolese. The General Superintendent of the quarry operation, R. V. Perini, said getting workmen was not a problem. Wages were about $1.60 per day per man for the 200 workers who were removing about 1,800 tons of stone a day. As more equipment was delivered to the quarry, it was expected that the work force would increase to about 300 men in midsummer of 1904.

Life on Johnson’s Island was not always kind to Mr. Zannetti. One incident made the August 18, 1912 edition of the Sandusky Register and could be called the beer crisis. The cost of a bottle of beer at the general store was 7 cents. Quarry workers found that they could buy a beer for less than 5 cents if they bought it in Sandusky and paid to have it shipped to the island. Mr. Zannetti’s only defense was that he had to pay for a license that cost $3.00 per day, and besides, the workers could well afford the extra 2 cents because they were saving a great deal of money on their meals. The matter probably was not resolved until Sandusky Bay became so rough that the small boat that delivered the less expensive beer could not reach the island.

Children of the quarry workers attended school while on the island. Miss Zelma Ramsdell taught at the island school.

According to the Sandusky Register, work would be plentiful for the next decade with 1,000,000 tons of stone needed in Cleveland alone, to finish its breakwater work. As the breakwater work was completed, production was reduced drastically in 1916 to less than one-third of the 51,000 tons / month required previously. In August of 1916, a fire of unknown origin destroyed the loading dock and the derricks and equipment used for loading stone. Finally in July of 1933, the last of the old quarry equipment was salvaged for scrap and the remaining wood structures burned.

The quarry remained inactive until the mid 1960s when work was started on the causeway to the mainland. Material left from the earlier quarry operations was used for this purpose. An attempt was made to restart quarry operations in 1977 for a breakwater job in Cleveland. However zoning laws enacted by Danbury Township prior to 1977, withstood the test of a long legal battle in the courts of Ohio, and the quarry once again was closed. Several years later, the quarry was changed into a basin for dockage of boats for a housing development in the area surrounding the quarry.