Island History – Civil War Era

Prisoner Of War Depot – Overview

Depot Prisoners Of War, Near Sandusky, Ohio

Considerations made for the choice of Johnson’s Island and the construction of the POW Depot

When the Civil War began, the Union felt the war would be over quickly. After the early battles in 1861, the War Department changed its thinking, realizing that the south had enough determination, men, and materials to continue the war for several months. Also, the Union was able to see that the war would involve the capture of thousands of Confederate prisoners. As a result, Col. William Hoffman was ordered to establish a system of prisons in the north to incarcerate the prisoners of war.

The Great Lakes area was seen to be a good location for a Prisoner Of War depot. The area was separated from Canada by the Great Lakes and far enough away from the southern battlefields to decrease the possibility of raids to release the prisoners. Also, the area was accessible for the transportation of prisoners. In the fall of 1861, Col. Hoffman toured the north shores of the Union to find suitable sites for prisons. In some instances, existing military camps were enlarged and utilized. In others, new prisons were erected.

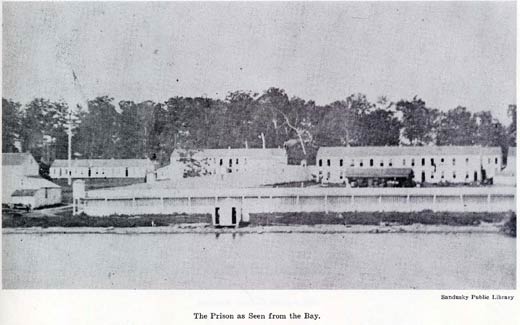

Johnson’s Island was chosen for a new prison site in the fall of 1861. It was an attractive site for many reasons. It was an island fairly well isolated, yet accessible by boat for most of the year. Accessibility was important to transport the prisoners quickly to the island and to supply food and materials for 3,000 POWs and a standing guard garrison of at least 1,000 soldiers. Also, in the event there ever was a riot or insurrection at the prison, Union Militia could easily reinforce the guard garrison. There was a forty-acre site already cleared on the side of the island facing the city of Sandusky which was only two and one half miles by boat from the island. Sandusky Bay was an excellent source of water for the needs of several thousand prisoners and the guard garrison. The city of Sandusky was a rail head, transferring goods to and from boats. The infrastructure needed for the transportation of several hundred POWs at a time was already in place for the most part. The island was inhabited only by the owner L. B. Johnson and his family. In addition, the military could control ingress and egress to the island. Even the Johnson family had to have permission to leave and return to the island.

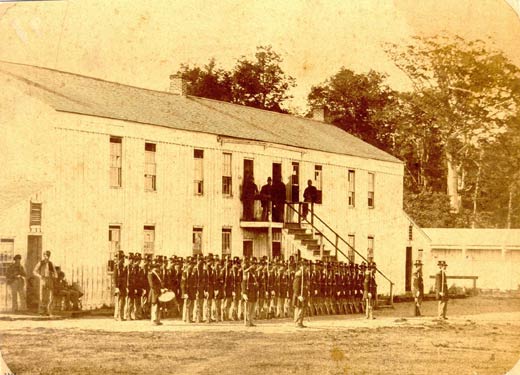

In November of 1861, work started on the guard barracks, prison stockade, and barracks for the prisoners. A total of 12 Prison Blocks of various sizes were constructed inside the stockade. An additional block, No. 6, was the prison hospital. Originally, the prison was to hold both officers and soldiers. The first four blocks were divided into smaller rooms to accommodate both officers and soldiers. The War Department then decided to imprison only officers at Johnson’s Island, and the remaining blocks were divided into three large rooms on each of the two floors. Each prison block had a kitchen at either end of the ground floor in which to cook meals. Due to the availability of materials and workmen and, most importantly, good weather, the stockade site was completed enough to accept the first prisoners by mid April of 1862. Most of them were captured at Fort Donelson and Island No. 10. The remaining work was completed after the prison was in use.

During the 40 months the Depot was in operation, over 9,000 prisoners crossed Sandusky Bay to the Federal Docks and then were confined in the twelve prison blocks inside the stockade. Periods of confinement varied depending on when the prisoners arrived. For the most part, the first prisoners in 1862 were exchanged after only five months while those arriving after Gettysburg in July 1863 stayed for 12 to 18 months. The average number of prisoners confined at any one time was probably 2,000 to 2,500. The maximum number confined was approximately 3,200 prisoners in January of 1865. This number was considerably larger than the capacity based on available bed space.

After the Civil War ended, the Prison Depot was decommissioned in September 1865. The last nine prisoners, including two diehards who refused to take the oath of allegiance and two who were charged with piracy, left the island on September 5th. The buildings, lumber, and surplus materials and equipment needed to run the prison were auctioned off during 1865 and 1866. Leonard Johnson, owner of the island, was the best bidder for the buildings and lumber, which he eventually sold. A few of the buildings were brought across the ice to Marblehead and used as dwellings. None of the buildings remain.

Life as a Prisoner of War on Johnson’s Island

The first prisoners on Johnson’s island were treated fairly well. Of course, one must remember that they were being held against their wills. Their rations were the same, in amount, as those given the guards, but were of the less desirable cuts of meat such as the backs, shins, and necks of beef and pork. Prison food could be supplemented by buying more palatable food such as canned fruit, sardines, and fresh fruit when in season, from the prison sutler. They lived in prison blocks that were the same as those in which the guards were living. Two men slept in each bunk. The bunks were three high. These prisoners came in April 1862 and, for the most part, were exchanged in September. They were gone before the harsh winter winds came howling across Sandusky Bay. Those who followed were kept for much longer periods – up to 16 months for some prisoners in late1863 and 1864 as a result of the slow down of the exchange of prisoners.

Prisoners were required to follow ten rules made by the first Commandant, William Pierson, dealing with their conduct while imprisoned on Johnson’s Island. These dealt mainly with when and where they could be outside their block; when lights were to be extinguished and prisoners were to be in bed; prompt and implicit obedience of the guard’s orders; and not crossing the deadline. The first nine rules were not all that bad. The tenth one was very severe to say the least. It stated that any prisoner failing to obey the first nine rules would be fired upon. This did happen several times, and in one case, took the life of Lieutenant Elijah Gibson of the 11th Arkansas. Gibson failed to obey a guard’s order to return to a prison block after curfew. Gibson’s remains are still on Johnson’s Island in the Confederate cemetery. Fortunately, all the guards did not enforce the rules to the letter. There are accounts of some prisoners being shot at close range and the mine ball missing so greatly that the POW felt either the guard missed on purpose or was the Union’s worst shot.

Prison life was severely impacted when the treatment of Union POWs in Confederate prisons such as Andersonville, Salisbury and Libbey, became known to the War Department. Rations were cut in half, and some items such as coffee, tea, and sugar were eliminated altogether. Prisoners were no longer allowed to buy food at the sutler’s store. However, they were still allowed to purchase such items as tobacco, clothing, pens, ink, and paper for letter writing. Packages from home could no longer include food and, much to the joy of the guards, items such as Virginia hams and alcoholic beverages were confiscated as contraband. However, even under these restrictions, the prisoners were eating better than many of those still fighting for the Confederacy.

Perhaps the worst condition the prisoners endured was boredom. There was not much to do between morning and evening roll call. The prisoners used the time in a number of ways. Most of the men wrote letters home to sweethearts, families, friends and those who might be able to help them with money, clothing, and food. Others kept diaries and /or journals that were published after the war, leaving a record of what occurred inside the stockade. Others spent the time planning to escape to either Canada or the south.

The more talented individuals participated in minstrel shows, and theatrical productions for which they wrote the text and /or songs themselves. The youngest prisoners were often chosen to play the female parts in the plays. The Y.M.C.A. even had a chapter on Johnson’s Island where its members gathered once a week to hear a report by one of their own regarding a number of different subjects. Several prisoners kept autograph albums, collecting the names of men with whom they had served as well as names of new friends they met on Johnson’s Island. The books were more like address books since, in many instances, they were signed with the name, regiment, rank, and hometown of the signer as well as where he had been captured.

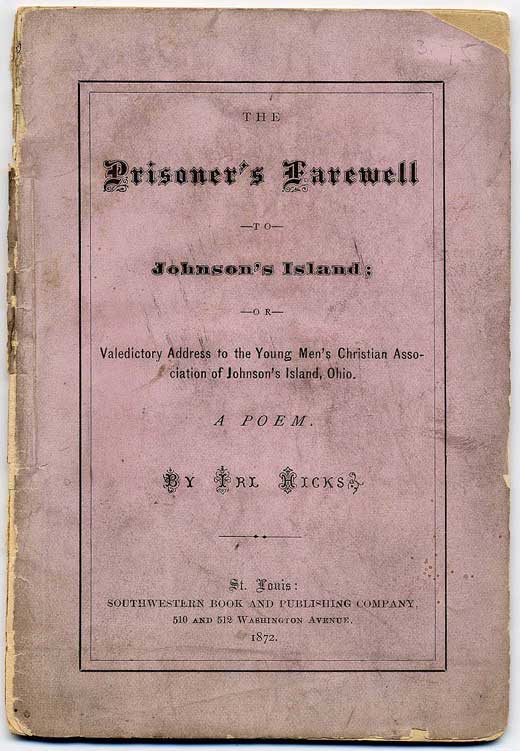

Many of the prisoners turned to expressing their feelings by writing poems. Many wrote about how much they disliked prison and longed to be home with loved ones. The most prolific poet was Major George McKnight of Louisiana who probably signed every autograph book being circulated while he was on the island. Most prisoners knew him as Asa Hartz. He participated in writing and producing several comedies in the confines of his prison block. McKnight placed an ad in the New York News for someone to substitute for him on Johnson’s Island who must be over 30 years old and have “A-1 digestive powers”. In return, he offered the advantages “of a strict retirement, army rations, and unmitigated watchfulness to prevent him from getting lost … for an indefinite period”.

The longest poem written on Johnson’s Island, to our knowledge, was by Irl Hicks It is a Valedictory Poem titled “The Prisoner’s Farewell to Johnson’ Island”. Hicks presented the poem on May 19, 1865 at the last meeting of the Young Men’s Christian Association Of Johnson’s Island.

Weather permitting; prisoners took part in many outside activities. Many enjoyed simply talking with each other about the status of the war, especially with the newly arrived “fresh fish” which was the name given to those who were recently captured and sent to the island. Baseball was learned and played by many in the narrow area between the rows of prison blocks. Many played chess and checkers in the warm, sunlit area by the prison blocks. Some took to gardening, growing tomatoes, greens, and peas.

There were many who were skillful in making furniture, maps, sketches of the island, as well as hats and clothing to wear or to disguise oneself as a guard to escape. A great many prisoners found satisfaction in making trinkets and rings from gutta percha (hard rubber) rulers and buttons (See image below of shield made on Johnson’s Island). Many fine rings were cut from hard rubber buttons which were carved to the size of the recipient’s finger. Then, many hours were spent inlaying mother of pearl, silver, and sometimes even gold, designs on the rings. The final product was then buffed to perfection for many hours before being sold to another prisoner or guard, or sent to the maker’s mother or sweetheart. Other prisoners carved lead bullets making such items as chess pieces, sinkers with which to fish and trinkets such as the pine cone shown below.

Religious services were held regularly by prisoners who had preached in the days before the war broke out. Many sermons were given from the upper landing of the outdoor stairs. Letters from some prisoners acknowledged that they had found a love for God while on Johnson’s Island. Bible study classes were held in the evenings during the week. The Official Records show that Fr. L. Molon, a Catholic Priest from Sandusky received permission from Col. Pierson to visit Johnson’s Island and conduct religious services. On May 11, 1863, Fr. R. A. Sidley was given permission to replace Fr. Molon.

Confederate Generals

During the forty months that the prison was in operation, there were fifteen Confederate generals imprisoned at various times. Nine officers of lesser rank imprisoned on the island were eventually promoted to general after they were exchanged. General M. Jeff Thompson was never officially commissioned by the Confederacy even though he was commissioned general in the Missouri State Guard. Two of the generals were Major Generals – Isaac Trimble and Alleghany Ed Johnson. Trimble was imprisoned for fifteen months whereas Johnson stayed only 16 days. The majority were brigadier generals when captured. Six held the rank of colonel or lieutenant colonel; one was a major and one a captain. Sixteen of the generals were captured in the western theater.

These men were very talented in both military and civilian life. They were highly educated, courageous and leaders who fought under the most demanding general officers such as Robert E. Lee and Thomas (Stonewall) Jackson. Of the twenty-five generals, eight were West Point graduates; three were Virginia Military Institute graduates, and seven were from other universities and colleges in Tennessee and Virginia. Alpheus Baker was home schooled, and M. Jeff Thompson was self-educated as a civil engineer while working on the railroad.

To obtain a complete listing of the Generals, please contact us at jipres@johnsonsisland.org for details.

Escapes from Johnson’s Island

Those who planned to escape and those who actually did

In 1863 and 1864, there were many prisoners who thought about leaving Johnson’s Island, with or without being exchanged. One group consisted of escape planners who organized the men into five details or groups from the 12 prison blocks. General Trimble was the ranking officer in charge but would not participate, nor order the men to attempt the escape. The reason was that one of his legs was amputated at Gettysburg making it physically impossible for him participate. The generals in charge of the details were M. Jeff Thompson, James J. Archer, William N. R. Beall, John R. Jones, and John W. Frazer. Each of the five generals then chose ten colonels whom they knew and could trust. The colonels then chose ten officers each whom they knew to be trustworthy. In this way a force of 500 men that could be trusted was created. Of the many plans that were discussed, the one that was adopted consisted of rushing the main gate when it was opened for the wagon carrying goods shipped by the Express company; then overpowering the guards and then rushing and capturing the steamer that delivered the express packages from Sandusky. Perhaps this was the best mass escape plan since the guard garrison on duty was only half of the Hoffman Battalion, about 200 soldiers. Once the prisoners had control of the island, they would sail to Sandusky and capture boats at anchor in the harbor. The boats would then take all the prisoners to Canada which was only a few hours away. Unfortunately the escape was delayed for three days because one of the groups was not ready. On the third day, the escape attempt was abandoned when the U.S.S. Michigan, with her 14 cannon, steamed into Sandusky Bay and anchored off of Johnson’s Island.

There were twelve prisoners known to have escaped from Johnson’s Island. Many more tried to leave but were apprehended before leaving the island. It is difficult to determine the total number of escape attempts, as some men realized they would be caught and therefore returned to their blocks before being detected. At times, the entry in the remarks column of the list of prisoners simply said – not here, must have escaped. Most of the successful attempts were by deception – dressing in clothing similar to the guards and walking across the ice to Sandusky or Marblehead, thence to points south to the Confederacy or north to Canada.

One prisoner, Lt .Charles Pierce, 7th Louisiana, was the most persistent and unlucky prisoner when it came to escape attempts. His seven attempts included tunneling, scaling the stockade wall and crossing the ice to Cedar point, and two attempts posing as a Union guard. Unfortunately, he was caught every time and remained on the island until the war was over. In contrast to Pierce’s bad luck is the experience of 2nd Lieutenant D. Woodson of Company K of the 28th Virginia. He was captured at Green Castle, Pennsylvania in February 1864. Fortunately for Woodson, he escaped on June 30, 1864, but the escape was not reported until July 2nd, 1864. Apparently, his prison mess mates knew how to keep a secret while they enjoyed Woodson’s rations.

Another hard luck prisoner was Col. D.R. Hundley who was commander of the 31st. Alabama Infantry. On January 2, 1865, Hundley, dressed as one of the guards who called the role of the prisoners each day, slipped out of the stockade gate. The guards were distracted by friends of Hundley’s who started a fight just as he reached the gate. The morning was extremely cold, and Hundley pulled the cape of his outer coat around his head so that the guard at the gate could not recognize him. Once out of the stockade, he made his way to the ice and crossed Sandusky Bay to the city of Sandusky. At the railroad terminal, he had second thoughts about taking a train to Detroit because of the number of Union soldiers at the terminal. Instead he started to walk in the direction of Detroit, through a blinding snowstorm, following the railroad tracks. To his disappointment, after walking for four days, he came to the city of Fremont which was only about 25 miles southwest of Sandusky. He was able to convince a hotel night clerk that he had fought at the front, and the clerk gave him a room. However after seeing a wanted poster for another prisoner, the clerk alerted the local authorities about Hundley. After some sleep and two good meals, Hundley was arrested and returned to Johnson’s Island. Hundley remained on the island until he was released on July 25, 1865.

Escape to Canada

Four prisoners were successful in escaping from Johnson’s Island to Canada in January 1864. Their journey started by scaling the stockade wall on January 1, 1864, one of the coldest nights ever experienced by the prisoners while on the island. Six prisoners started, but only four made it all the way to Canada. Led by Major John R. Winston of North Carolina, the group scaled the stockade wall late in the evening, during the change of guard. One of the group, Major Stokes dropped out quickly because he felt he was not dressed warmly enough. Captain Thomas Stoakes set out by himself to cross Sandusky Bay after being seen by a guard. The remaining men, Major Winston, Captain G. H. Davis, Lt. C.C. Robinson and Captain J. H. McConnell, crossed the ice of Sandusky Bay to the Marblehead peninsula. They then walked to Port Clinton, stole two draft horses and eventually made it to Detroit without being detected. All that remained was to cross the Detroit River which was not frozen solid. They accomplished this by jumping from ice slab to ice slab and finally set foot in Canada.

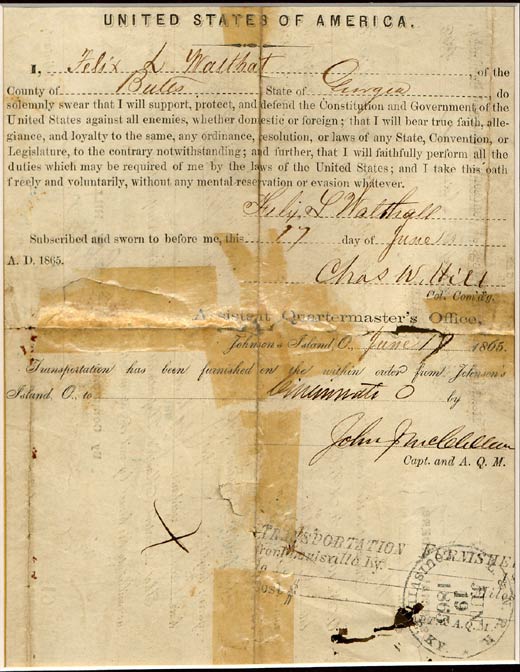

Oath of Allegiance

In addition to escaping, there were three other ways to leave the island; by exchange or parole; by death; or by taking the Oath of Allegiance to the Union. Any of the more than 9,000 men confined on the island at one time or another could have secured his release by taking the Oath Of Allegiance to the Union. However, the fierce loyalty and devotion to the Confederacy can be seen in that only about 50 men did so prior to February of 1865. Any prisoner applying to take the Oath had his name posted prominently about the prison quarters for all to see. Those applying were moved to prison block #1 for their own protection until such as time as they took the Oath and left the island. Before returning home, anyone taking the oath had to serve one year in the Union Army first.

The 1864 Raid on Johnson’s Island

The most complicated attempt to make a mass breakout of prisoners from Johnson’s Island occurred in September of 1864, when a small group of 30 Confederates from Canada commandeered a ferry boat, the Philo Parsons, to cross Lake Erie to Sandusky. The group was led by John Yates Beall who was qualified for the raid by his success in Chesapeake Bay as a Privateer. Confederate Charles Cole, who had a dubious military reputation, was in Sandusky, and had the job of gaining the confidence of the officers of the U.S. S. Michigan which was armed with fourteen cannon and was the only gunboat on the Great Lakes. The Michigan was anchored in Sandusky Bay to provide additional protection to Johnson’s Island. Cole, who was posing as a wealthy oil man from Pennsylvania, was to drug the officers the night of the raid thereby making it possible for Beall to seize the Michigan and force the Commandant of Johnson’s Island, Lt. Col. Charles Hill, to release the prisoners. Once this was accomplished, sailing vessels in Sandusky harbor would be seized and used to remove the prisoners from Johnson’s Island.

Unfortunately for the Confederates, one of their party, who was an informant, alerted the Provost Marshall Generals office in Detroit about the raid. Assistant Provost Marshall, Lt. Col. L. B. Hill, telegraphed this information to Captain John C. Carter, Commander of the Michigan. Cole was arrested before he could perform his part of the plan. The Confederates on the Parsons, anchored off Sandusky Bay, and waited in vain for a signal from Cole indicating they could enter the harbor and take over the Michigan. After a few hours, they realized something was very wrong and that it was senseless to continue with the mission. The Confederates headed northwest to the Detroit River, where at Sandwich, Ontario, they scuttled the Parsons and headed for Windsor, Ontario.

To obtain more information about this raid, please contact us at jipres@johnsonsisland.org for details.